Loch Fyne Whiskies, The George, The Ben Nevis

Tasted in February

Travels along the west coast of Scotland in February afforded us a night in Inveraray, a regular pit stop for whisky pilgrims en route to Islay and Campbeltown. We had booked a room at The George Hotel, one of the Highland’s oldest and most notable country inns. Having only ever called in for a cheeky pint over the years, we were excited to finally be spending the night, even more so given the laurels they’d recently earned as SLTN’s Whisky Bar of the Year.

The George is an institution in Argyll known for both its food and traditional pub vibes, so there was no surprise to find it overflowing on a Saturday night, even in February. In business since 1860, crossing its threshold is like stepping onto the set of an historical romance with deer antlers adorning thick stone walls, a multitude of cozy snugs, roaring peat fires, and an ambiance as well trod and well worn as its rough hewn floorboards. W Hotel mavens need not apply; history is steeped in every nook and cranny of The George, with antique curios and intricate carvings framed by its massive wooden beams. A castle for Christmas? Yes please!

We had wisely booked for dinner (reservations are recommended throughout the year) and found ourselves seated in the restaurant with a clear view of what The George casually terms its ‘Cocktail Bar’. The general mood was jubilant, and all around us merrymakers were tucking into espresso martinis (why?) and pints of beer, no doubt well earned after the rigorous discipline of a dry January. Charles followed suit with an IPA, meanwhile my eyes adjusted their focus to scan the alluring selection of whisky, for the most part official bottlings from across Scotland as a whole. As much as the phrase is overused, I always admire a well curated bar, and here multiple expressions from the same distillery offered endless possibilities for vertical tastings. Even more welcome was seeing a thoughful clutch of world whiskies that went beyond Japan: Lot 40 (yay!) Balcones, Michters, Stauning (boss!) Kavalan, Aber Falls. For a moment I got my hopes up; I’ve been jonesing for something from White Peak after a glowing recommendation from a cooperage in Portugal last year. I scanned the bar again, but unfortunately no dice.

After a most excellent pair of venison burgers, our server helpfully directed us to The George’s Public Bar, “where the really good stuff is kept,” he winked. We made our way through a warren of stone and emerged in a modest pub housing a treasure trove of whisky that immediately impressed, though not for quantity. To be clear, two hundred bottles and counting is not an inconsiderate sum (in the Public Bar alone; another two hundred plus reside in the Cocktail Bar.) However, it was quickly apparent that The George had foregone the usual whisky arms race that afflicts other establishments. In its place was a thoughtful breadth that favoured smaller independent bottlers and ‘second growth’ distilleries — Ardmore, Arran, Craigellachie, Benrinnes — alongside official bottlings from newcomers like Nc’nean, Lagg, Ardnamurchan, Torabhaig, Raasay, and Lochlea. With a clear focus on the west coast, peat, Islay and Springbank were plentiful, yes, but so was Glen Scotia in equal measures, though in truth they had me with their rich selection from Loch Lomond, including multiple Croftengea and the seldom seen Old Rhosdhu.

Our admiration of the pub’s gantry was cut short by a 300-strong Netflix crew wrapping up a film shoot, and we suddenly found ourselves in a human crush pinned against the bar. Despite the pandemonium, Charles’ Lagavulin t-shirt had acted as a beacon, and in short order a friendly bartender took note and made his way over, introducing himself as Ivan. “Welcome to my playground!” he beamed, raising his voice over the crowd.

A true professional, Ivan was unflappable as he juggled pints and worked the bar optics in between showing us bottles and answering questions. He apologized for the helter-skelter nature of the bar that evening, and asked for our patience, suggesting that things might calm down once the band got started upstairs. “Normally I have four or five whisky lovers lined up at the bar, and we geek out,” explained Ivan, identifying himself as a kindred soul who had come to Scotland from Italy to pursue his passion for whisky, “but at the moment I’m pouring shots!”

In truth I was more disappointed by the lack of proper copitas than the thirsty crowd, but was keen to get stuck in some drams given how busy the bar had become. As he is wont to do, Charles got down to business quickly, unearthing a sweetheart in the form of a peated Ardmore 12 Year Old from the new-to-us Bramble Whisky Co. In the meantime I was loving the lemony biscuit nose of my Candlekitty 18 Year Old, but getting impatient with how long it was taking to open up and offer the round waxiness I look for in a Clynelish, so I took to whinging about the glassware again.

The George’s ‘Malt of the Moment’ was Lochlea, a distillery we’d been crushing on since our first dram at the beginning of this trip. We opted for a vertical tasting that started with their very solid core expression Lochlea Our Barley (mmmm…) moving onto the Lochlea Harvest Edition 2nd Crop (more please!) a malt which thoroughly delighted, despite my initial concern about too much wine. This was the case with the Lochlea Fallow Edition 2nd Crop, a touch too heavy on the PX for either of our liking, though make no mistake, we ploughed through every drop (see what I did there?) That every dram managed to make itself heard through the din of an increasingly raucous Saturday night was no small feat, and left us in no doubt that Lochlea is a distillery to watch.

Charles has the dubious ability to attract strangers in bars, and tonight was no different, as he was quickly cornered by a gruff crew member with steely eyes. He noticed our empty glasses and ordered Ivan to pour us more of the Lochlea that he too had been drinking, because malt-of-the-moment and all. He proceeded to lecture us on real whisky, single malt whisky, the stuff they drink in Scotland, his unwavering devotion to his wife after 32 years, and how building sets for ‘The Crown’ had paid his mortgage down South. As some of the “lazy actors” made their way to the bar, we learned that he had no time for “that lot”, nor “vegans, I mean Jesus Christ, what even is up with that?”

The idle blether took a sharp left turn as our bar mate bemoaned his inability to get a US working visa due to a history of violence on his criminal record. Right; it was time to go, so I handed the rest of my Lochlea to Charles and started inching away. “Oh, so now you’re giving away my whisky, are you?” the violent criminal offender snarled while baring his teeth, confirming my hunch that it was time to leave. Thankfully, it was a rhetorical question; he turned his back in a huff and rejoined his mates. Relief. I retrieved my glass from Charles and savoured the last bit of Lochlea’s gingery, malty goodness. Now it was time to go for real, so we thanked Ivan and waved goodbye as he apologized once again. “I’m so, so sorry! Tonight it’s all about gin and vodka, but please come back another time!”

We awoke Sunday morning too late for breakfast, so checked out of The George on an empty stomach, promising ourselves that we’d return and put the whisky bar through its proper paces. As we headed to our car hire I took a moment to gaze longingly across the street at Invereray’s original whisky landmark, Loch Fyne Whiskies, on most days signposted by the statue of a greeter named Hamish, itself another village landmark.

Although it is now under the umbrella of The Whisky Shop chain, Loch Fyne Whiskies was the world’s first specialist whisky store when it was established in 1993 by Richard and Lyndsay Joynson. It quickly earned its reputation as a sanctuary for whisky lovers, as well as launching one of the first retail websites from where they spread the gospel of uisge beatha around the world via Royal Mail. Indeed I count myself as one of their early disciples. Twice yearly they would publish their highly respected print newsletter, the aptly named Scotch Whisky Review. Originally meant for their regular customers, the SWR became a font of knowledge widely read by those both in and out of the industry, and could easily be considered Scotch whisky’s earliest source of dedicated drinks journalism.

Since its original proprietors retired in 2013 much has changed, both for the shop and whisky at large, as auctioneers, Amazon, grocers and distillers themselves crowd what was previously a niche market. Not to mention flim-flam artists, I thought to myself, recalling our previous visit. It coincided with a Peter Lorre doppelganger asking staff if they knew of any ‘high-net worth individuals’ that might be interested in ‘discreetly’ acquiring a collection of very old and rare bottles that he’d been safeguarding in South America. “Believe me, I can make it worth your while,” he assured staff who, to their credit, took his business card with a straight face.

Hamish was nowhere to be found out front, but a sandwich board suggested that the shop was already open this early on a Sunday. Like moths to a flame we stepped inside for old times sake, if only to pay homage to where our fascination with malt whisky truly jumped off. We said our hellos and started browsing the hallowed space in silence. As always I looked overhead to review the Collector’s Loft, a feature introduced by Richard Joynson who, in hindsight, was an early visionary in recognizing the inherent worth of Scotch whisky as a collectible. Richard had a particular knack for identifying bottles that would accrue in value, and while the Loft carries on in name, for longtime whisky lovers the current selection is a pale imitation of its former glory, though just as intimidating in its pricing.

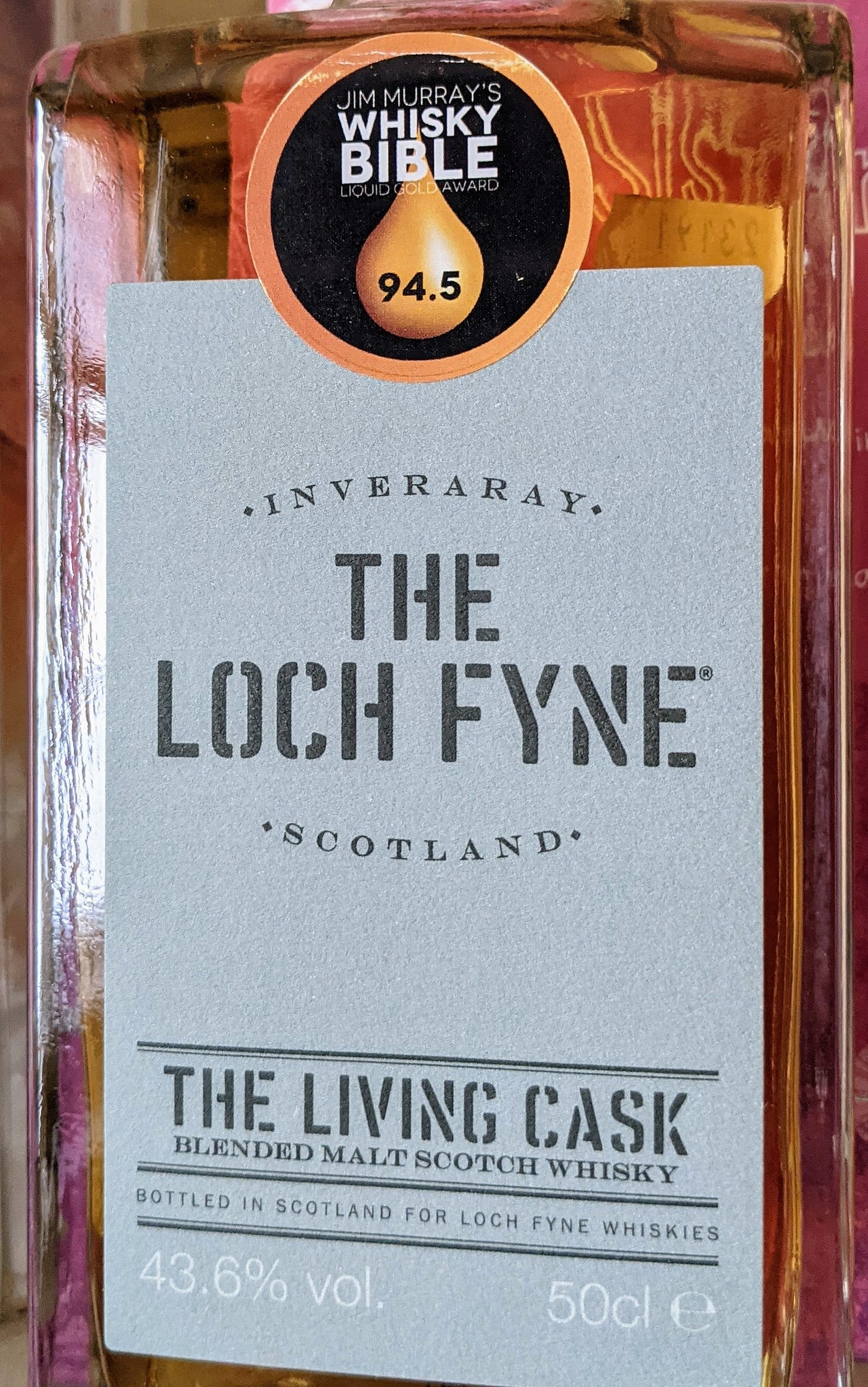

Charles wandered over to the Living Cask, a leftover bit of Richard’s ingenuity based on his reading of George Saintsbury’s Notes on a Cellar-Book whereby the author describes a solera system of whisky that evolves as new malt is introduced once the cask is half full. It’s always heartening to see that the Living Cask continues, but I noticed for the first time a series of casks bottled under the Loch Fyne name, the side hustle of most retailers these days as they compete in an uncomfortably cramped marketplace.

Our shopkeep seemed somewhat aloof, but one could hardly blame him this early on a Sunday morning; given Invereray’s tourist traffic, this shop must see its fair share of tire kickers. Since we had yet to make a purchase under its new ownership that made us tire kickers, too, but then Charles spotted their own label Ben Nevis 1996 and started asking questions.

Questions led to samples which led to banter which led to more samples. Having asked about Hamish (“he’s off sick at the moment”) we were recognized as more serious players, and in turn more samples were offered. We tried a Springbank 1993 from a bourbon cask which our new friend Kenny deemed as “fine, but not worth the price,” and I had to concur, after searching for the coconut and fruit to no avail. He then handed Charles a sample of their The Living Cask 1745, 43.6%, which in its latest iteration was a vatting of four 18-year-old casks of whisky from Islay. I immediately took a step back because mystery Islay malts are too often code for Caol Ila, but one sip made the argument moot. Hello coconut! Hello fruit! Could that be you Kilchoman? And is that a refill butt lurking in the background?

I don’t gamble, but imagined that finding this kind of needle in a whisky haystack is what it felt like to come up with a row of 7’s at the slot machine, first thing on a Sunday morning. Here was an incredibly lush, juicy personification of Islay that slinked across the palate with its silky mein as we both swooned. Meanwhile I daydreamed of a peated, fortified perry, one with a never-ending finish that belied the relatively small sip we were each afforded. I further noted with impish pleasure that the bottle had the audacity to sport a label from Jim Murray’s Whisky Bible, awarding it 94.5 points — not that scores are my jam, but I applaud anyone with the guramba to push back against cancel culture.

Kenny had us in the palm of his hand and knew when to hold them, so to speak. Next up was a sample of Ledaig 26 Year Old, 65.6%, and I stood riveted given that a Ledaig 1973 from a sherry hogshead is in the top echelon of my most memorable malt moments. Bottled as part of its Fynest Series — the branding for LFW’s crème de la crème — the label doesn’t lie: spellbinding is the watchword here, along with peat, liquorice and espresso. And as just one of 427 bottles, such auspicious numbers confirmed our second purchase of the morning.

Sensing that I was in dangerous company I decided it was time to fold them and walk way, before any more damage to my credit card could be done. But this wasn’t Kenny’s first time at the rodeo; after bagging our purchases he poured yet another sample. “Obviously we’ve already done a bit of business here, but you seem to know your whisky, and truly, this Glenrothes 18 Year Old, 55.7% is just stunning...” I lowered my head in resignation. I had met my match, and accepted defeat with the same aplomb as I accepted this dark and heady Glenrothes from a first-fill American oak sherry cask. ‘Alas Glenrothes, I once knew you well’, I thought to myself, remembering those halcyon days when the ‘70s vintages were aplenty and the Select Reserve was most respectable, before a series of underwhelming age statements appeared. And whatever happened to Ronnie Cox anyways? Time really does fly. Certainly a pandemic doesn’t help.

I told myself that having Charles pay for the Glenrothes would somehow allow me to save face, and then we made our way to Glasgow via brunch at Loch Fyne Oysters. Tables are impossible to come by in the high season, so we patted ourselves on the back for braving the Scottish winter as we filled up on oysters, cullen skink, smoked salmon (three ways!) and kedgeree done right.

Quiet bickering ensued on the approach to Glasgow upon realization that we’d run out of room in our luggage and would need to buy another piece. Glasgow always feels anticlimactic after time spent in the Highlands, and I was irritable just thinking about wandering the city centre in search of an Argos. In the end it was much ado about nothing; parking was plentiful on a Sunday, which left ample time to get to the hotel before dinner, where Charles carefully packed our bottles (one his many whisky superpowers, for which I am grateful!)

Glasgow was mild and lovely that evening, and we decided to wander about on foot in search of dinner. Even in winter we still couldn’t get a table without reservations at the much vaunted Ox and Finch, so we settled for curry and naan at Mother India, though we barely managed to sneak in before they too were full. Given that it was Sunday night in Glasgow, we headed to The Ben Nevis after dinner for a nightcap with live music. As luck would have it, the musicians were tuning their instruments right as we arrived and we snagged ringside seats at the end of the bar. Noticing the newly released Lochlea 5 Year Old on the shelf, Charles ordered one straight away and even got it served in a copita — braw!

After sampling more than four dozen whiskies in less than two weeks, palate fatigue had set in, so I scanned the bar for alternatives. Scotland is having a spiced rum moment, so I crossed my fingers in hopes of finding Deer Island from Jura, a gorgeous thing, beautifully balanced with dried orange peel and cardamom, and all but impossible to find off-island. Failing that, I wondered about the excellent Islay Rum Peat Spiced that we’d enjoyed at the Lochside Hotel the previous week. There was no luck on either front, so I opted for Dark Matter, another respectable Scottish spiced rum that was sweet without being cloy. Served on ice, it was a solid choice for a digestif after dinner, but it still went down a little too easily so I switch to whisky, this time a Lochlea Cask Strength.

No less than ten musicians poured their hearts and souls into their axes as they vibed with the crowd, some of whom were stepping in time to the basic patterns of Scottish country dance. The music’s rhythm was exhilarating, and when the guitarist broke into vocals for a solo, the room fell into a hushed silence as he sang in proper Scots, both stirring and mournful at once. The timbre of his voice echoed across the room, and my eyes welled with tears as I let both the music and whisky move through me, the two combined providing catharsis for what had been a traumatic start to this year.

In between sets we enjoyed banter with some of the players when Richard, on banjo, noticed our copitas, and immediately wanted to know what we were dramming. Another kindred soul, Richard had moved from Northumberland to Aberdeenshire for “work and whisky,” and his passion for the latter had really taken off, though trad music was a close second that regularly brought him to Glasgow “as nothing beats the music scene here,” and he was buzzing just to be playing with “this bunch, I mean most of them are from the Conservatoire.”

Richard agreed that the energy of the night’s session was electrifying, the best he’s witnessed in a very long time, and when the jam was done he entreated us to stay awhile longer, please just one more dram, the round was on him. His enthusiasm was infectious and an apt reminder of why whisky is dubbed the water of life. It turned out that Richard quite fancied a sherried dram and he was treating himself to an Arran 17 Year Old the colour of treacle, “a stunning whisky though I have no idea of the price, they can get up to twenty, even thirty pounds here, depending on the bottle!”

The mood was real and righteous, and I knew that we could easily make more friends, nevermind doing a deep dive into Lochlea with a vertical tasting of every bottle lining the shelf. But with an early morning flight, we were wary of how (and when) the night would end so reluctantly said goodbye, though given our shared love of whisky and trad, I was hopeful that our paths would cross again.