Laphroaig 6 Year Old, 50.8%

And the band played on…

Facts: a dunnage warehouse is probably the worst place to taste whisky, hashtag unpopular opinion! And this is coming from someone who avails herself of any and every opportunity to tread these hallowed grounds. No, the sheer romance of visiting a genuine warehouse is not to be missed, if only to take a deep breath and lose oneself in the headiness of its damp air and reverential silence, bearing holy witness as the alchemy of spirit, wood and time conspire.

That said, the cold, the draft and the dim lighting quickly combine to dull the senses, making a warehouse one of the absolute worst places for the considered appreciation of any spirit, but particularly one as complex as Scotch whisky. This in no way denies the allure of enjoying a dram in situ; few whisky lovers would argue against the gratification to be had from offsetting the damp cold with the heat of a full proof dram, especially one drawn from a cask that holds special meaning. But the fact remains that a cold whisky is a closed whisky, both on the nose and the palate, and warming the liquid in hand soon becomes tedious when drawing upon the reserves of your own internal thermostat.

As £18 tours become £50 experiences, a number of distilleries are clocking this fact, customising spaces within former or present warehousing to sell the romance and ambiance of a warehouse with a modicum of comfort. At Laphroaig it’s an antechamber at the entrance of Warehouse 1 that sits on the water’s edge, outfitted with tables, chairs and steel bars that allow paying guests to gaze longingly at the casks, while keeping their paws off the distillery’s precious wares. While it no doubt works for the majority of visitors, in truth I felt left out in the cold, so to speak, like a scullery maid in the kitchen, spying on the lobster and laughter of a dinner party, the mouth salivating as the mind imagines the taste of these untold riches, so close yet so far.

Back in the kitchen tasting room, we were handed a valinch to draw whisky from three duty-paid casks: a 7-year-old whisky fully matured in an ex-Makers Mark bourbon cask, a second 7-year-old whisky from a virgin French oak cask that had been charred, and a 6-year-old fully matured in a Fino cask, also charred. To a tee all three whiskies were hot and immature, and none were recognizable as Laphroaig given the heavy-handed clubbing of oak. Disappointment set in soon after: there would be no insight into the whiskies used to blend Laphroaig’s core range, or limited editions such as the annual Cairdeas. There would be no taste of a cask from Laphroaig’s own floor maltings. The location was the experience, full stop. Suddenly £90 felt like an outrageous amount for such a meagre selection of whisky, regardless of where we were seated. Meanwhile, inside the warehouse proper, the band played on.

After voicing my dismay at the samples on offer given the price of the tour, our guide quickly put me in my place: “Our master blender would disagree with you.” Having enjoyed Laphroaig longer than his blender had been in the industry, it was tempting to respond that I looked forward to him becoming better acquainted with his own stock. But as Cyrus Redblock would say, “civility gentlemen, always civility”, so I kept my churlish thoughts to myself and sat in a sulk.

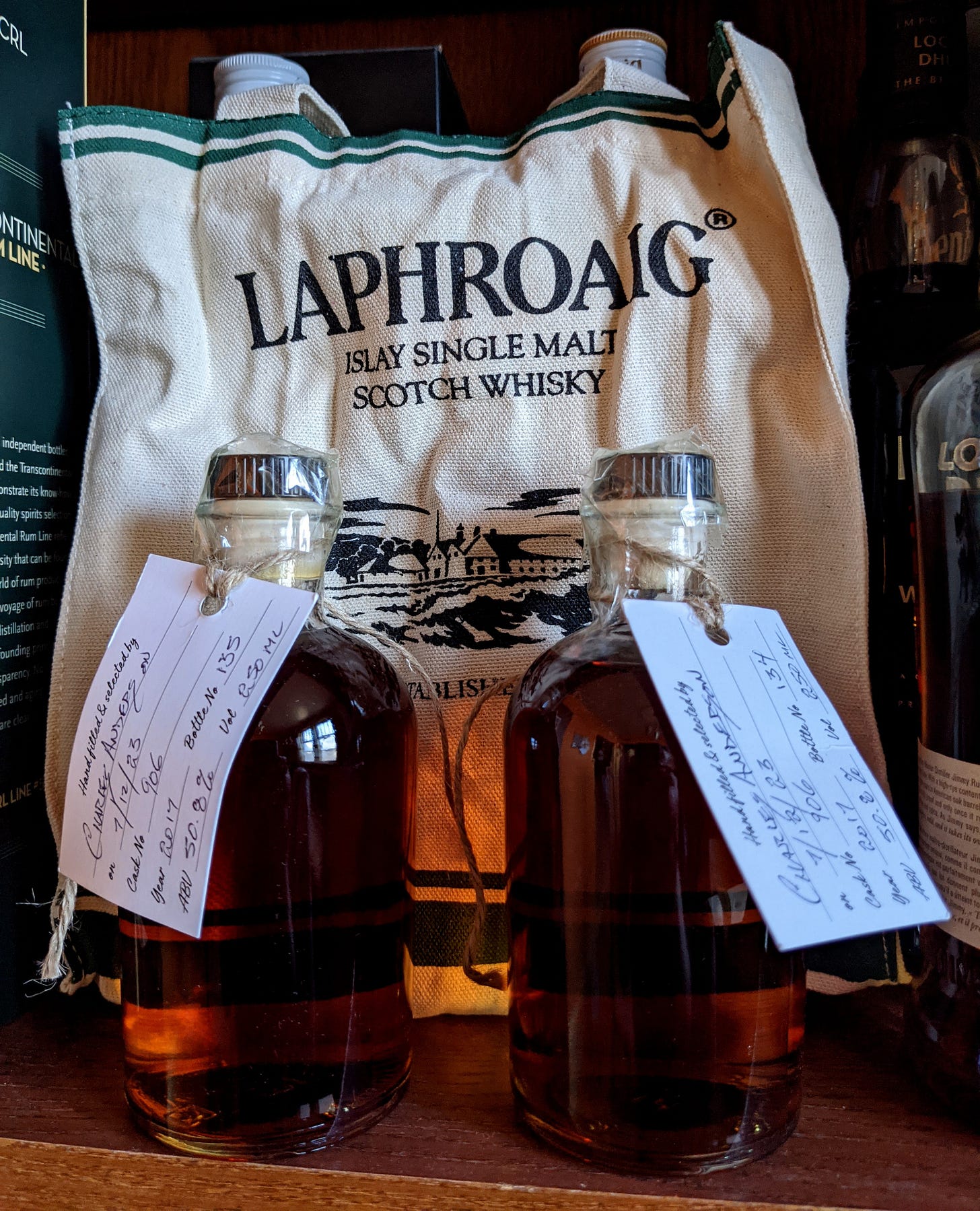

The £90 tour price included a 200ml sample drawn from our favourite of the three casks, and much to our guide’s consternation I stood my ground and politely declined the giveaway. Ever the optimist, Charles broke the impasse by filling both our sample bottles with Laphroaig 6 Year Old fully matured in a charred Fino cask, in his opinion the least hot of the three, and whisky that should make decent blending stock that he’ll use to hone his skills over the winter. I look forward to reporting back on the results, and maybe even bringing back a sample to our esteemed guide upon a return visit.