“Excuse me, I’m looking for Iain McArthur?”

We’re two left turns off Port Ellen’s main drag. Iain McArthur — Lagavulin’s former warehouse manager, recently retired after 53 years making whisky — had said to come find him the next time we were in town, so that’s us trying to figure out where exactly Iain lives, but to be fair it wasn’t the first time a local had given us vague directions. It’s the Islay way, it seems.

The two gentlemen break their chat, looking perplexed and bemused at the same time. I immediately wonder if it’s my hat, which isn’t a common sight on Islay, even in winter. On second thought, neither is an obvious stranger meandering their hood after dark.

“Right. So you mean Pinky? Blue van over there.”

We head to the blue van, turn up the walkway and knock on the door. No answer, but I’m feeling too ridiculous to give up now so head to the back door where the lights are on. Mrs. McArthur opens the door quizzically with ‘Pinky’ standing behind her, his five-foot-three stature belying his outsized wit and personality. Clearly wandering about residential streets knocking on doors isn’t the done thing on Islay, but neither of them seems perturbed. “It’s the Canadians!” Iain exclaims. “Well it’s my birthday, come on in!”

Sitting in the McArthur living room feels warm and familiar, like visiting with a favourite aunt and uncle at Christmas. As I sink into the cushions of their sofa, I finger the knots of its afghan throw and realize that I needn’t have felt ridiculous at all. We were being proffered Highland hospitality by people who favoured genuine ‘face time’ versus the artifice of Facebook, and they’re eager to know where we’ve been on Islay and who we’d spoken to so far. “So that’s you at Bruichladdich today? Who took you around? Aye, Ashley, she’s a Port Ellen girl.” Iain nods and acknowledges her as one of his own, reaffirming my hunch that despite being a small island, Ileachs maintain a particular loyalty to their respective villages.

It’s a refreshing antidote to the elitist one-upmanship of Scotch whisky, and I notice my breathing had slowed as I continue to sip the mulchy, oddly rustic Lagavulin Feis Ile 2022 that Pinky had poured for us. “Nae, that one’s not great,” Iain confirms, and we all laugh out loud at the candour for which he’s become famous. “Well then, isn’t that just grand of you to have poured it for them?” Mrs. McArthur breaks in, the two of them well rehearsed in their back-and-forth. “Aye, well, it opens up and rounds out as it sits in the glass, but you need to give it some time,” Iain offers in his defense — not that one was needed; in this moment it’s a whisky that tastes of hospitality, and is made all the better for it.

Iain may have been retired but he’s still a ‘whisky man’ through and through, as we trade the names of mutual acquaintances and offer updates on their last known whereabouts. “That was Jim McEwan getting on the ferry last week,” Mrs. McArthur chimes in from her TV chair. “Didn’t even say hello, looked quite busy.” I mention Ardnahoe and Iain cuts in sharply as he brings us up to date. “Oh, best not mention Ardnahoe to Jim,” Iain shakes his head, “he has nothing good to say about them.”

While unspoken there’s the distinct sense that Iain may have retired from ‘working for the man’, but somehow wasn’t done with whisky at large. “Aye, there’ve been offers,” Iain shares casually, with the relaxed demeanor of someone who knows they have options if they so choose. “I’m taking it easy for the moment. Let’s see if something interesting comes along.” Iain’s eyes twinkle as he smiles, and it’s infectious.

I feel very proud to have been at Lagavulin distillery for so long, although it doesn’t feel like work to me. I just get to spend my days doing what I love — working with whisky and people.

“I was over at the new distillery Tuesday to pick up some draff for my cattle, aye. It’s not been officially opened but they’ve started running the stills, so I got to try the new make — aye, it was a bit feinty, but don’t tell anyone I said that!” Iain chortles. “Nah, it’ll be alright, I’m sure they’ll get it sorted in time!”

Talk of process and production turns to changes in the industry that Iain reckons we’ll be noticing in the bottle in a few years’ time. “Aye, it’s changing,” he notes of the beloved Lagavulin 16 Year Old. He reminisces about his start in the industry, of finishing school at sixteen on a Friday and being told to report to Port Ellen’s warehouse the following Monday after his mother ran into the distillery manager while she was working as a cashier at the co-op. “I was as big as the barrels then,” Iain laughs. I ask who’s been hired for the reopening of the distillery and Iain admits he doesn’t know many of the staff. But wouldn’t you put your most senior whiskymakers on the job to resurrect such an iconic distillery, I wonder out loud? Surely you’d want your most experienced hands in place?

“You’d assume as much, but that’s not how senior management thinks,” Iain explains as he reflects on changes in the industry. “See, company policy is aiming for fifty-percent women in production roles by 2030.” Iain pauses, understandably given that diversity hires are a sticky subject. “So there’s change afoot, there’s no doubt. And that’s fine. But here’s the thing: you can’t just have young’uns running the show.” He sits up straight for emphasis. “You need experience; you’ve got to have old hands on board to show them the way!”

Whiskymaking on Islay has been the same for generations. It’s this tradition and skill, gifted down through our forebears who worked at Lagavulin, which means we still produce today what they perfected hundreds of years ago.

After fifty-three years working in the industry, the accolades have been plentiful and Iain is enjoying his laurels, a testament to the many lives he’s touched throughout his career. He gets up to show off some of the various mementos he’s been gifted, including a photo of the prized bull his friends had brought to Lagavulin on his last day of work. “Now that wouldn’t have been cheap, a good thousand pounds there.”

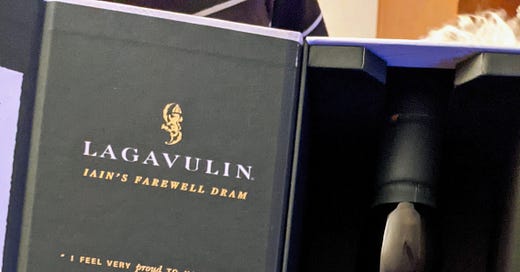

He then takes a case off the shelf and opens it to reveal ‘Iain’s Farewell Dram’, an 18-year-old Lagavulin finished in an ex-Manzanilla cask.

I immediately gripe about the fact that those of us who attended his farewell Christmas tasting had the opportunity to sample it, but weren’t given a chance to put our names in the lottery to buy a bottle. “Don’t even get me started,” Iain rolls his eyes and grunts. “Friends and family, they called this bottle. They never should have done that. Do you know how much grief I’ve gotten over this whisky? What a headache this bottle has caused. For a good month folk were after me everywhere I went. ‘Hey Iain, aren’t I your friend? Where’s my bottle?’ At the co-op, at the post office, on the street — ‘hey Iain, we went to primary school together, aren’t we mates?’ Thank God I don’t go to the pub. It was an effort just to get a second bottle for my daughter.”

I inquire as to where these bottles ended up. “Who knows! Mostly within the company from what I can tell, eighteen held back by the distillery for a lottery, and only for locals. And they wouldn’t even let me put my name in for a chance to get an extra bottle!”

In the background I can hear Mrs. McArthur sigh and cluck, at the same time; she’s heard it all before, and clearly none of it comes as a surprise. But despite the palaver his retirement whisky has caused, it’s obvious that Iain is chuffed at being memorialized with his likeness on a bottle, and he holds out his legacy in its handsome packaging. “Go on,” he beams with pride, “take a picture!”

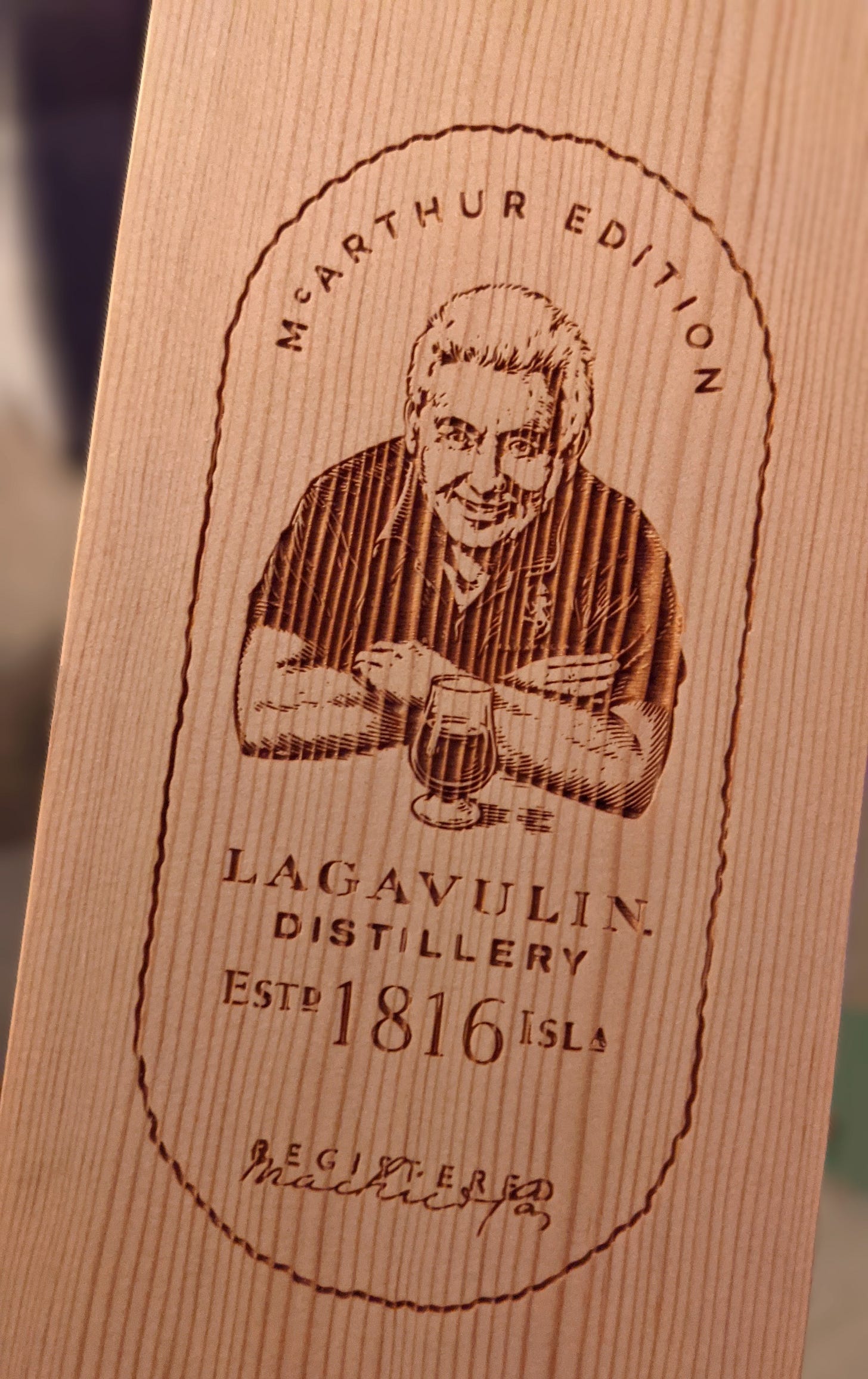

“Now,” he says leaving the room to fetch something from his credenza, “take a look at what came in the post!”

Iain returns and proudly holds out a wooden case with the front label of ‘Iain’s Farewell Dram’ laser engraved on the front panel. He turns it over to show off the backing. The box was fashioned by the Offerman Wood Shop and is a gift from actor Nick Offerman, who played Lagavulin aficionado Ron Swanson on the tv sitcom Parks and Recreation. A personal message from Nick Offerman has been inscribed:

Dear Iain,

Thank you kindly for sharing your twinkle, your expertise, and your charisma with our pageants over the years. Our adverts will be considerably less handsome in your absence.

Slàinte Mhath,

xo Nick Offerman

As cliched as it seems to impart an aura of wisdom to our elders, I can’t help but ask Iain what parting advice he would give to the industry that he served for fifty-three years. As with everything about ‘Pinky’, his words and mannerisms are humble, but belie a much larger message:

“Be nice.”

Iain speaks slowly and plainly, but the eloquence comes through in the conviction of his words.

“I tell people, you be nice to those who are coming to visit us. But so often people don’t get it, and I have to keep reminding them. ‘Oh, there’s another group from China,’ and I say I don’t care where they’re from, they’re buying our whisky and now they’ve come all this way to see us. I can’t say it enough, you have to be nice to folk who make the effort to come see us in person.”

It strikes me as such simple advice that it could be mistaken for a platitude. Yet for someone who has lived through the pain of a whisky loch; for someone who witnessed firsthand their community lose its livelihood as a knock-on effect of people turning away from whisky in droves — such unabashed gratitude makes perfect sense. For the moment Scotch whisky may reign supreme but it hasn’t always, nor can its current adulation be taken for granted. I can’t help but think that in light of Iain’s ‘lived experience’, his plainspoken, simple words are worth barreling, as much as the new make flowing from the stills at the newly resurrected Port Ellen. Who knows, maybe some much-needed humility might even coalesce.

“Just be nice. These people are buying our whisky, and making the effort to come see us. But they didn’t have to. Never forget that.”