Chartreuse, An Abbreviated History

A look at the monks, methods and mystique behind France's most beloved liqueur

Reprinted from Distilled, Issue 2

Words by Johanna Ngoh and photography by Olivier Parent

Everything comes to an end.

A good book, a balmy summer’s day, a fine bottle of wine.

Life.

It’s not a matter of if, but when, and prolonging the latter has been an obsession of the human condition since the dawn of time, most notably in the case of nobility.

King Henry IV of France would have been no different in seeking out longevity, and as such there was doubtless little fanfare when the brother of his favourite mistress — the Marshal d’Estrées — arrived at the monastery of Vauvert bearing a cryptic manuscript promising just that: an elixir of long life. The year was 1605 at which time Paris was home to an outpost of Carthusian monks, formally known as ‘Les Frères des Chartreux’, an order founded by Saint Bruno in 1084 to pursue silence and solitude in the name of God.

While it might seem odd to have been seeking spiritual contemplation in the middle of Paris, the city walls had literally grown up around the monastery, situated in what is now the Luxembourg Garden. Being located in the Latin Quarter, just steps from the Sorbonne, had its advantages, giving the monks ready access to research and news of the world as it was unfolding at that time. And in the age of alchemy, when the line between mysticism and science was blurred, the monks had become most famous for their apothecary, botany and distilling being its specialties.

Whether the Marshal was acting as the King’s messenger was never conclusively established. Despite the monastery’s academic renown, the complexity of the document and its esoteric ingredients proved unintelligible, and it lay dormant for the next 130 years before being transferred to the Order’s headquarters, the motherhouse known as La Grande Chartreuse, nestled in a pre-alpine valley within the Chartreuse Mountains. It is here that the monks would succeed in distilling the medicinal tincture that forms the basis of the herbal liqueur known and loved the world over as Chartreuse.

Speculation abounds as to the origins of such an elaborate list of 130 plants, herbs, spices and flowers from four continents, said to be a compilation of all botanicals with medicinal properties known to the Middle Ages. Both history and geography point to the ancient city of Constantinople, at one time a major junction on the Silk Road, known as the ‘city of plants’ given its busy trade in horticulture from around the world. It was also a buffer between Europe and the Arab empire, where distilling for medicinal purposes had been taking place for more than a thousand years.

While Brother Jerome Maubec has been given historical credit for first deciphering Marshal d’Estrée’s document, in truth it was the culmination of several monks’ research and adjustments, some passed along on their very deathbed. The manuscript’s first realisation – as per its original instructions – was in fact recorded as a disappointment, with a bitter, acrid taste and an unappetising rust colour, though the monks were impressed with its therapeutic properties and research continued.

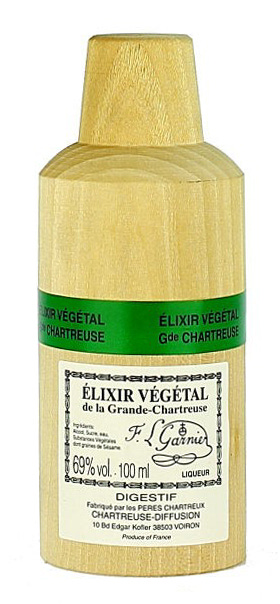

Further modifications were made, and what was originally a five-step process became eight, which further multiplied as successive monks applied their refinements to the formula. In 1762 the base of modern-day green Chartreuse, known as ‘l’Élixir Végétal’, was bottled in tincture form at a proof of 71% abv. It continues to be sold in French pharmacies to this day.

Once sweetened for taste and lowered to 55% abv, the elixir was commercialised two years later at weekly markets in Grenoble. This new and improved product – promoted as a ‘health liqueur’ – was eagerly received by locals, and word of mouth grew its popularity quickly.

By 1840 the monks had again expanded their product range, with a sweeter version still, yellow in colour and bottled at a gentler 43% abv. It was an immediate success that was quickly nicknamed the ‘Queen of Liqueurs’, outselling its green predecessor three to one. It’s at this time that the monks underwent their first marketing exercise, eschewing the moniker of health liqueur in favour of the brand name ‘Chartreuse’.

Mystery vs Method

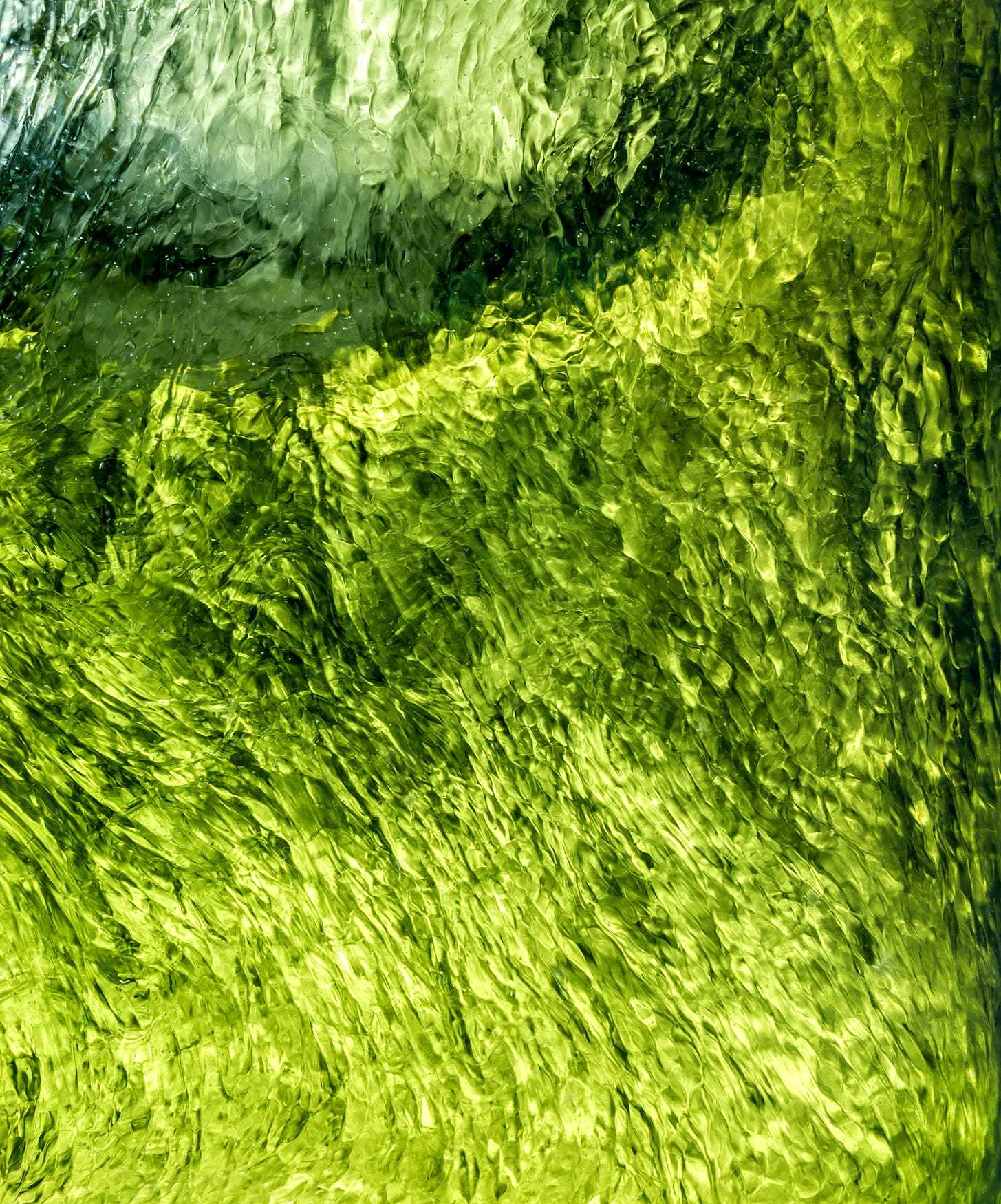

The Chartreuse Mountains are both majestic and haunting, breathtaking in size, and a humbling reminder of our diminutive stature next to nature. It’s a setting that naturally lends itself to contemplation and is credited with bestowing the Chartreux monks with an ability to see, hear and understand the world at large with open minds in their pursuit of knowledge and excellence.

The Order as founded by Saint Bruno was always meant to be self-sufficient, funded by the monks’ labour rather than donations or alms. Since 1084 the monks have worked as farmers, cattle breeders, and blacksmiths, making swords for the Knights Templar fighting in The Crusades. And now for more than 250 years they are distillers. It is an apt vocation in a region previously known as ‘Le Dauphiné’, acclaimed for its gastronomical bounty including cheese, nougat, chocolate, wine and liqueurs, of which Chartreuse is one of many produced in the area.

Much has been made over the centuries as to the mystery surrounding France’s most beloved and enduring liqueur. It’s a turbulent history fraught with duplicity, legal setbacks, religious persecutions, politics and war. Imitations throughout its 400-year history have been rife and trademark infringements became par for the course.

The Carthusians have gone to great lengths to guard its secrecy: the original manuscript remains hidden within the monastery in a folder that includes more than two dozen pages of original notes detailing the exhaustive research carried out by successive generations of monks, and there is the know-how of more than two hundred years of production which has been passed down by oral tradition.

Two-thirds of the raw material used in making Chartreuse come from its immediate mountain range, and it’s a popular pastime among residents to guess which native plants find their way behind the locked doors of the ‘salle des plantes’ at La Grande Chartreuse, to which only two monks have access. Here, in the monastery’s former bakery, the liqueur’s production is currently coordinated by Dom Bénoit and Brother Jean Jacques, who receive weekly deliveries of botanicals in plain paper bags marked only by number.

These are subsequently dried, sorted, weighed and milled, before being blended in varying combinations and ratios. Confidentiality agreements are signed by the monastery’s suppliers, though local foragers have long been known to provide the monks with ‘vulneraria’, a medicinal plant native to the French Alps, as well as oregano, which grows in abundance around the monastery.

Once the botanicals are prepared and blended in the correct proportions, numbered sacks are sent thirty kilometres away to the Chartreux distillery in Voiron. Here three laymen work under the direction of Brother Jean Jacques in executing a labyrinthine series of macerations and distillations. The art and science of extracting the botanicals’ essence is exacting, and applying the correct sequence and variables is at the heart of the liqueur’s secret. “In reality making Chartreuse is far more complicated than anyone can imagine,” Brother Jean-Jacques is known to have said on numerous occasions.

The distillery workers use both an eau-de-vie and a purer beetroot alcohol to variously distil or macerate these secret batches of botanicals, with each base extracting a plant’s essential oils at different rates and to different degrees. In working with their two stainless steel alembic stills, distillation temperature and speed are equally critical and adjusted continuously as per the monks’ instructions.

The Carthusians further maintain a laboratory at the monastery with a remote workstation that allows them to monitor temperature and ethanol levels among other variables, though analysis and correction must be done on-site, for which Brother Jean Jacques visits weekly.

Chartreuse has become as famous for its colour as for its legend and lore. A final maceration of the distillate over an undisclosed ‘number of days’ yields its yellow and green hues. Saffron has been confirmed in the case of the former, but those closely connected to the monks patently refute the popular notion that spinach is used to colour the green liqueur.

The final spirit is then piped from the still room to the distillery’s underground cellars and stored in vats made of European oak, where the sugar, plant essences and alcohol are left to marry. It is the largest such cellar in the world, with two million litres of liqueur lying in rest. The monks do not adhere to a fixed maturation schedule: yellow Chartreuse is aged for an average of two and a half years and the green for three and a half, while older variants of both, bottled by vintage under the rubric VEP – ‘Viellissement Extra Prolongée’ – are aged for anywhere from eight to ten years.

Contemplation versus Commerce

Merging monastic life with commercial enterprise has always presented the Chartreux Order with a unique set of challenges as it sought to uphold Saint Bruno’s tenet of self-sufficiency.

Proceeds from the current production of Chartreuse are essential in contributing towards the maintenance of more than 350 monks and twenty-three monasteries worldwide. But labour – whether making liqueur or hewing lumber – is interpreted as a spiritual pursuit, and the Carthusian distillers view their activities with humility, seeing this work no different than that of their brothers toiling in the garden or baking bread.

“Work is important to us for two reasons. Firstly monks have to earn their keep,” Dom François-Marie Velut explained in a televised interview with Canal 4. He works in the Order’s carpentry shop building the embossed wooden boxes used to package the liqueur’s VEP bottles. “But it also allows us to exercise the body while freeing the heart and the spirit for contemplation. For this reason monks enjoy simple, repetitive work that can be done in silence for hours and hours, allowing one to pray or to simply feel God’s presence.”

Yet the paradox in producing a social lubricant in order to preserve an ascetic existence did not go unnoticed by the Vatican. As Chartreuse grew in popularity and production escalated, Pope Pie IX intervened in 1860, instructing the Order to build a separate distillery outwith the walls of La Grande Chartreuse. Not only was the noise and commotion of their on-site facility deemed to be an interference with the pursuit of silence and solitude, but the production of alcohol was seen as an inappropriate activity within the confines of a charterhouse, running contrary to the maxim of austerity as set out by Saint Bruno.

Ten years later the Vatican intervened once again and the monks were ordered to appoint a layman to handle sales of the liqueurs. It is a practice that continues to this day through Chartreuse Diffusion, a secular company of which the monks are majority shareholders, established in 1970 to oversee the sales, marketing and distribution of all the Order’s products, as well as the distillery’s visitor centre.

Collectors and Connoisseurs

Along with renewed popularity thanks to a resurgence of cocktails such as The Last Word, interest in Chartreuse has been buoyed in recent times by an active collector’s market. The Order has released limited editions and special cuvées since the early 1900s, but for both the collector and connoisseur Chartreuse’s real appeal – and mystique – lies in its on-going evolution once bottled, through continued maceration of the botanicals.

Devotees agree unanimously that with time Chartreuse gains in finesse and evolves a greater complexity on the nose and palate as more subtle, secondary aromas make their way to the fore. Collectors have noticed a patina developing after fifteen years in bottle, though tasting VEP Chartreuse – generally aged from eight to ten years – can provide a more immediate assessment of the impact of time on the liqueur. Yellow Chartreuse is most notable for this effect given its lower alcohol proof and higher sugar content, said to better ‘eat its sugars’, an expression used by French oenophiles to describe a wine that has continued to evolve in bottle through a continued interaction between sugar and alcohol.

Many sommeliers maintain that this transformation makes old bottles of Chartreuse as diverse as wine, with variations from yellow to green, as well as years in bottle, vintage, and in particular what was made in France versus what was made in Tarragona, Spain, where the monks distilled Chartreuse from 1903 to 1989, with vintages from the fifties and sixties being held in high regard. The latter are famous for an unforgettable mouthfeel, an exceptionally long finish and astronomical prices, with a private cellar of fifty-six bottles recently auctioned by Christie’s for more than €150,000.

Whether the liqueur being made at present will mature into the same nectar as bottles from the fifties and sixties is up for debate among serious connoisseurs. Many lament that the distillery replaced its copper pot stills with stainless steel in 1990, and still others complain that the most recent production of Chartreuse has relied too heavily on the more neutral beetroot distillate as opposed to eau-de-vie which yields a better maceration and development of flavour in bottle over time.

“Does modern Chartreuse have the soul to be a future treasure, to be cellared for our grand children?” asks Michel Steinmetz, a collector and author of ‘Chartreuse, Histoire d’Une Liqueur’, the definitive tome on the subject. “Most connoisseurs agree it’s unlikely, making today’s vintage bottles all the more precious.”

The Perfect Pour

Current sales of Chartreuse top more than one million bottles per year, 30% of which is sold in the United States. In its reincarnation as a cocktail ingredient Green Chartreuse now outsells Yellow two to one, but for true fans the perfect pour of Chartreuse is served neat at room temperature, or chilled from the fridge, preferably not colder than 5°C according to purists. A popular serve is the ‘Episcopal’, combining one part yellow to two parts green Chartreuse, or the ‘Pontifical’ for those in the mood to splurge, using the above ratio with the extra-aged VEP variants. Still others keep l’Elixir Végétal on hand, adding a few drops to enhance the herbal bitterness of yellow Chartreuse.

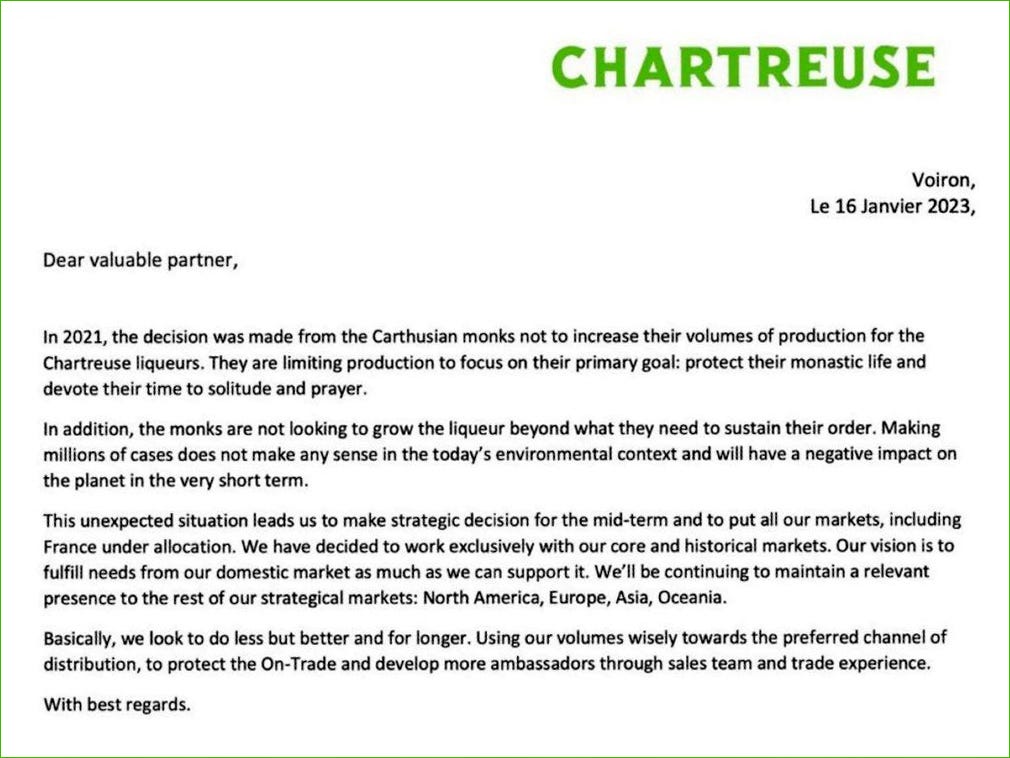

But regardless of how it’s served, the continued fascination with this relic of the past has been both universal and timeless, so much so that in January 2023 the monks took the significant step of capping production volumes despite the increased demand for their liqueurs, as outlined in a letter to on-premise customers that serve Chartreuse to thirsty patrons.

A victim of its own success, moving forward the Chartreux order is limiting its production activities as they seek to prioritize solitude and prayer, as well as protecting the environment from the negative impact of producing increased volumes, as well as the conditions of their monastic life which are focused on solitude and prayer.

It’s a fitting and welcome epilogue for a commodity that continues to survive in an age of instant gratification, in itself the proof of long life.