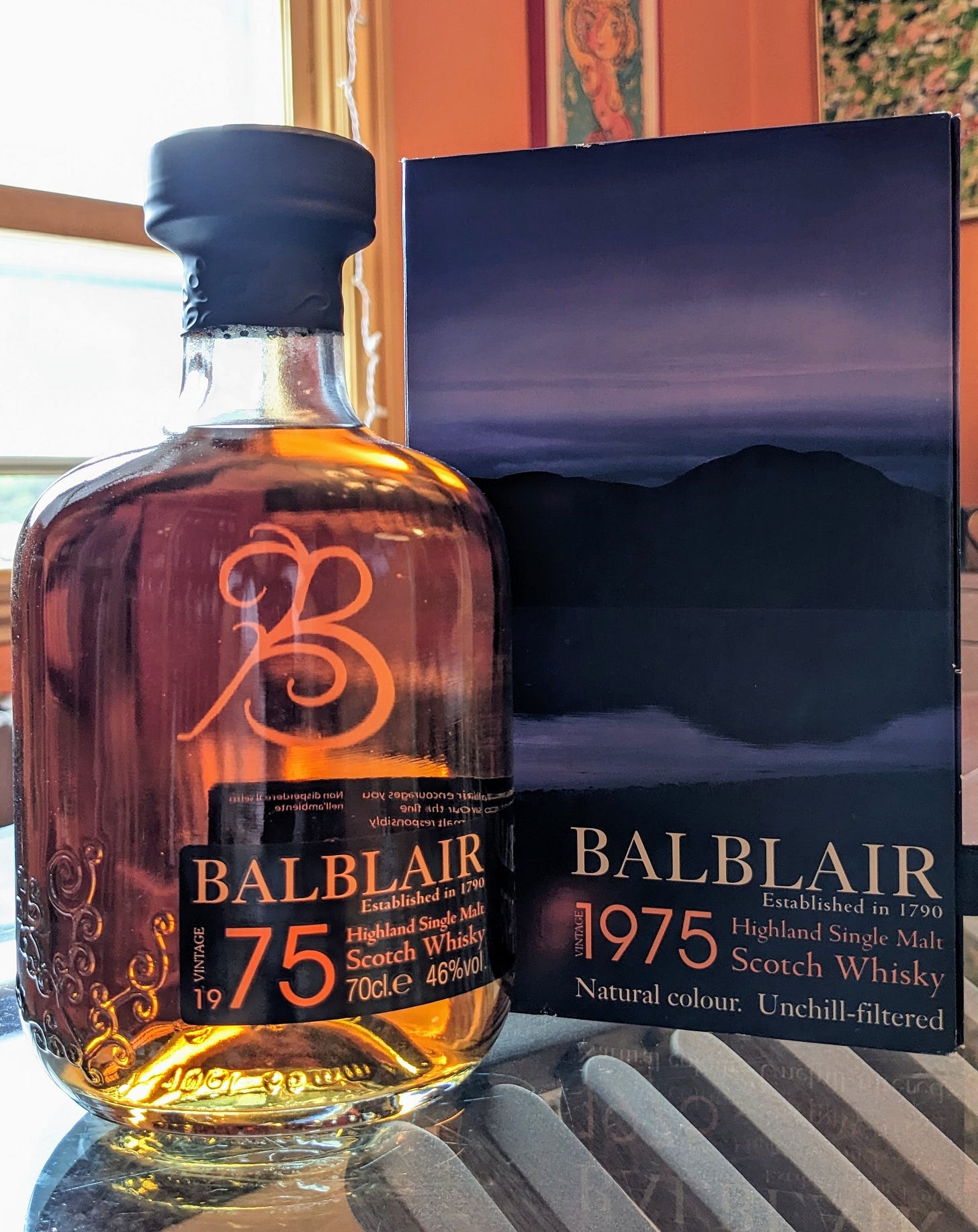

Balblair 1975, 46%

Reflections on the end of an era

Recent news of John MacDonald’s retirement as manager of Balblair Distillery took me aback; per our last exchange he still had a few more innings to go, though life has a way of throwing us curveballs as I’ve learned firsthand.

Waxing nostalgic, I recalled meeting John for the first time in 2007 when he was launching Balblair’s new core range as a series of vintages, the most memorable being this Balblair 1975, a truly sublime, luxuriously sherried malt that rivaled the best that Scotland had to offer at the time. It was his wife’s favourite whisky, John shared, and it became one of mine too (though the Balblair 1989 was certainly no slouch.)

The entire range of whiskies was thoughtfully made and thoughtfully packaged, un-chillfiltered and of natural colour, and John presented them with the pride of a new dad, understandably as he was credited in the liner notes for selecting the casks. Ever the sucker for a soulful watercolour, I never tire of the misty panorama of the Dornoch Firth wrapped around the outside of the box, with two of its vertical panels held in place by magnets, opening like double doors for the big reveal.

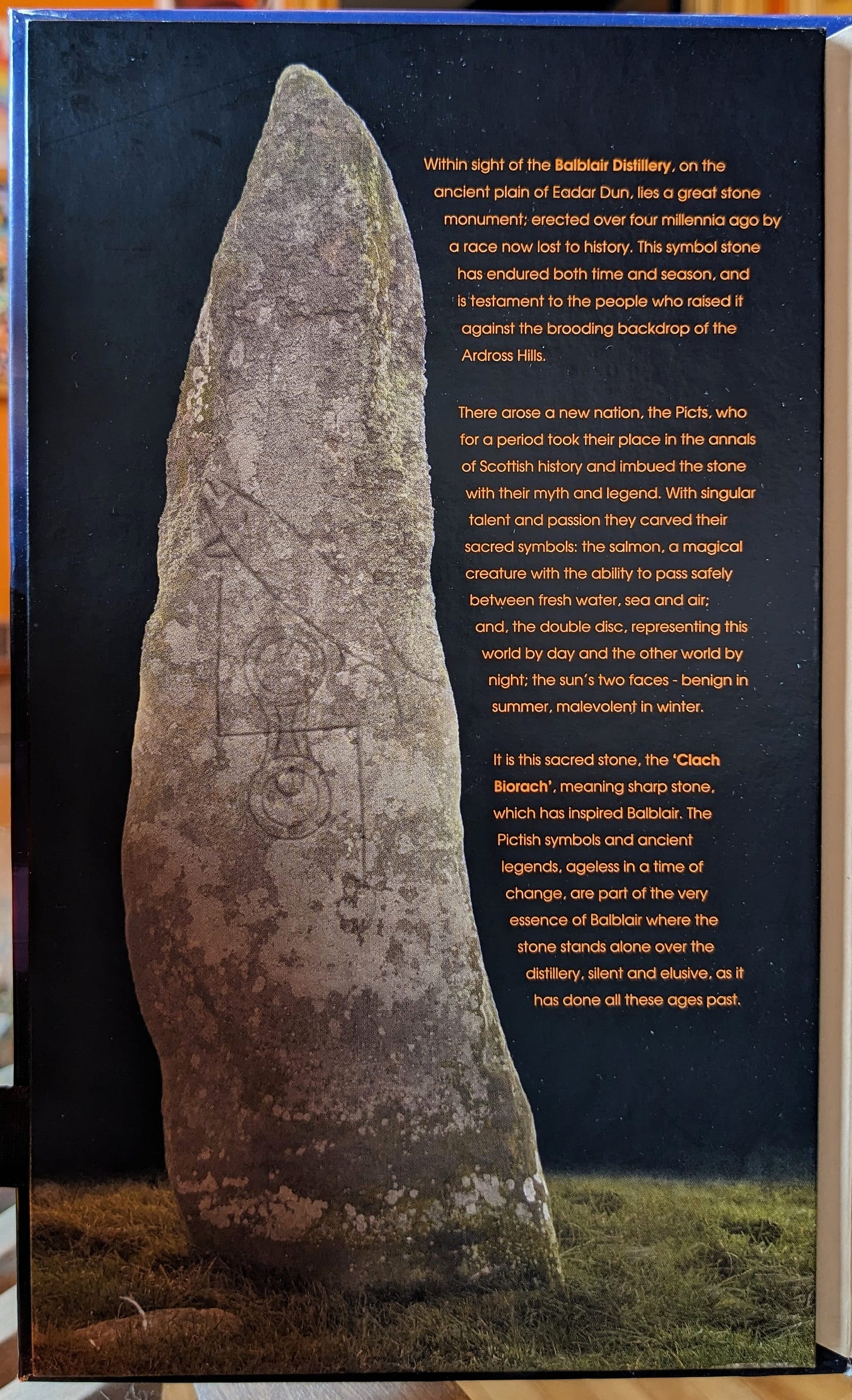

Those of you who groove on Highland Park’s Viking lore will be smitten by the standing stone located next to the distillery.

Balblair’s vintages borrowed liberally from this Pictish heritage, with the stone acting as a frontispiece inside the box, and a Pictish translation of the name Balblair thrown in for good measure:

Clever packaging and Picts aside, my takeaway from John’s tenure is of a manager that was very much the epitome of the whisky he shaped at Balblair – an elegant and pensive malt of depth. It also occurred to me that while whisky purists dissect the minutiae of process, barley, yeast and peat to the nth degree, there is seldom a mention of the terroir contributed by the people who make the whiskies we so enjoy.

These whiskymen as I call them (and whiskywomen — I regret having only ever exchanged emails with Maureen Robinson before her retirement) became not only the stewards of their respective distilleries, but custodians of its savoir faire. It’s a French expression that has come up repeatedly in conversation with European distillers, and one that continues to elude me in English. While its literal translation would be ‘know-how’ or ‘expertise’, to my thinking this inadequately suggests a strictly cognitive skill set, negating the passion, instinct and feel that one gains from the repetition of dirtying your hands week in, week out, year in, year out. Not unlike the concept of woodshedding, it’s the mastery born of repeated practice, something that can’t be replicated by taking a certificate course at the Institute of Brewing & Distilling and then appending the credential to your bona fides.

By contrast whiskymen like John are all but extinct; that ilk whose uncredentialed careers were moulded by the sweat of hard graft – what John called the traditional route – mentored by those who came before them, as they developed their intuition and feel for uisge beatha one cask at a time.

But time marches on, and with it comes a changing of the guard. What impact this will have on the whisky being barrelled for the next generation remains to be seen, and tasted. John had all the confidence in his team, in particular his assistant manager, Norman Laing, so there’s every reason to believe that Balblair is in capable hands moving forward. In the mean time I look forward to reading the book he promised to write, as per our last exchange. A condensed version of this conversation is posted here.